ISRAEL

– THE LAND AND ITS PEOPLE

Part

One

Laurie

Eddie

(Investigator

170, 2016 September)

THE LAND:

Located

at the eastern end of the Mediterranean, between the coast and the

Jordan River, and occupying much of what was once ancient Canaan, (an

area extending from the Sinai to Syria), lies that region of Western

Asia known as Israel. Part of the larger Levant region, (meaning -

"where the sun rises" or "where the land rises out of the sea"), this

area now includes modern Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Syria, Jordan and

northern Arabia.

This

region has long been historically important as it was one of the major

routes for early hominins migrating out of Africa and, as early as 1.8

million years ago, it was the location of some of the earliest hominine

settlements outside of Africa. Much later it would be the location of

the most profound social change in all history. At that time, nomadic

humans began to abandon their hunting-gathering existence in favour of

a sedentary agrarian lifestyle; in doing so they ushered in the

Neolithic Age and laid the foundations for civilization.

The

area, between the Levant and Mesopotamia, (Greek for, "between

rivers"), much of which includes the "Fertile Crescent," covers

approximately 980,000 km2 (378,380 square miles), is similar in size to

South Australia. For thousands of years it was the scene of almost

constant conflict as different cultures sought to control the region.

Apart from Egypt, which dominated much of Canaan, from the 22nd century

BCE onwards, the various competing groups included the:

•

Eblaites (3000-2300 BCE),

•

Sumerians (2600-1900 BCE),

•

Akkadians (2334-2154 BCE),

•

Amorites (2100-1700 BCE),

•

Hittites (1600-1178 BCE),

•

Hurrians of which the Mittani (1500-1300 BCE) were the most

influential,

•

Phoenicians (1500-800 BCE),

•

Assyrians (2500-612 BCE).

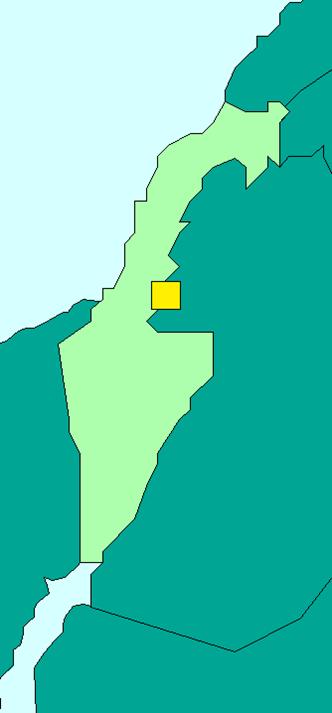

Occupying

only a small part of this region, the current State of Israel is a mere

470 km. (290 miles) in length, north to south, some 135 km. (85 miles)

across at its widest point, and occupies a total land area of only

22,145 km2, (8,630 square miles).

The

geographic structure of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Jordan,

is very similar, consisting of, "… a limestone substratum beneath a

thin terra rossa topsoil," (Coogan, 1998, p. 4). Terra rossa (Italian

for “red soil”) is produced when limestone weathers over millions of

years leaving clay and other non-soluble materials behind, producing a

red clay soil which is, "… best suited for olives and grapes and for

sheep and goats." (Coogan, 1998, p. 4) Later, under the Philistines,

the coastal region in particular, with its deep rich soil, would become

renowned for the production of fine wines, wheat and olives.

Israel

itself has three distinct agricultural and climatic zones, a

subtropical coastal region, the mountain district and the Jordan Valley.

Along

the Mediterranean coast are the fertile coastal plains, Shefelah and

Sharon; a narrow strip of land, ranging from 40 km. (24 miles), in

width in the south at Gaza, to a mere 5 km. (3 miles), in the north.

According to Coogan (1998), "In antiquity it was wetter than now, even

swampy in places…" (p.4) which made it an ideal location for

agriculture.

Located

to the east of the coastal plain are the hills of the Central

Highlands. They run south-to-north from the Negev to Samaria, before

turning in a north-westerly direction towards the Mediterranean. With

an average height of 610 metres (2001 feet), and with poor quality soil

and largely infertile, this was the area referred to in the Hebrew Old

Testament as, the "hill country" (Genesis 12:8). According to Easton

(1897),

"In

Deut. 1:7, Josh. 9:1; 10:40; 11:16, it denotes the elevated district of

Judah, Benjamin, and Ephraim, which forms the watershed between the

Mediterranean and the Dead Sea." (Palestine, Easton, 1897)

It

was, from these Central Highlands, according to Hackett (1998), that

the Israelites emerged in the twelfth and eleventh centuries. (p.132)

The

third region, the Jordan Valley, is part of the great Syrian-East

Africa Rift, running from near Antakya, (formerly Antioch) in Syria,

through the Red Sea and into East Africa. The valley stretches some 100

km. (62 miles), from the southern outlet of Lake Kinneret (the Sea of

Galilee), to the Dead Sea. Several degrees warmer than surrounding

areas, with good soil and a reliable water supply from the River

Jordan, it has been used for agricultural since circa 10,000 B.P.

Much

of the remaining land is wilderness and desert, suited only for the

most basic subsistence farming. At the southern end of Israel is the

Negev region, (meaning "barren country"), covering some 13,000 km2

(5,020 square miles). It is an area of such poor quality it is suited

only for grazing small cattle.

East

of the rift valley are large areas of semi-arid desert terrain while to

the south-east lies the vast Arabian Desert, an area of some 2,330,000

km2 (899,000 square miles), stretching from present day Jordan to Yemen

and Oman on the Arabian Sea. A desolate region, with limited rainfall,

it was suited only for nomadic and semi-nomadic groups such as the Arab

tribes, who from the 9th century BCE, (Eph'al, 1984), were constantly

on the move with their herds of goats and sheep seeking fresh pastures.

All

agriculturally based cultures require a harmonious balance of sunshine

and rainfall, and for Israel these come from what are, in effect, two

distinct seasons, a dry, hot summer, abruptly followed by a cool, wet

winter.

Both

the Canaanites and Israelites relied on their "gods" to send the annual

rains, "…he will give the rain in its season, the early rain and the

later rain …" (Deuteronomy 11:14). One of the most important Canaanite

gods was Ha Ba'al, or Hadad, who had dominion over fertility and rain,

(Canaan, EB, 2015). The "divine" deliverance of rain was just as

important for the Israelites; as Jeremiah commented,

"Are

there any among the false gods of the nations that can bring rain? Or

can the heavens give showers? Are you not he, O Lord our God? We set

our hope on you, for you do all these things." (Jeremiah, 14:22)

Like

their non-Jewish neighbours, the Israelites believed their prophets

could intervene with god to make it rain. (1 Samuel 12:18).

Rainfall

usually began in late October or early November, these "first rains" "…

loosens the dry earth for plowing," (Jacobs, 1907). Heavier winter

rains follow in mid-December and continue through to January, (see Ezra

10:9 and 13), "... for behold the winter is past the rains is over and

gone". (Song of Solomon 2:11). Follow-up rains come in April-May which

encourage the growth of the grain.

Rainfall

throughout the land varies quite considerably, Weinberger, et al.,

(2012) reported that it varied,

"…

from approximately 1000 mm in the northern mountains (upper Kinneret

and western Galilee), to 500-600 mm in the Yarkon-Taninim basin, the

central mountains and the Coastal basin. In the southern Negev and

Arava regions the annual rainfall is usually below 50 mm." (p. 11)

For

most of the year the water courses throughout the land are dry

riverbeds, (wadis), however, during the rainy seasons they fill and

burst their banks. Judges 5:19-21 describes how, during a battle at

"Taanach, by the waters of Megiddo," the better-armed, and chariot

equipped Canaanites were defeated by the Israelites after they were

caught by a flash flood in the Wadi Kishon, and, " ... the torrent

Kishon swept them away." (5:21)

Some

70% of all the rainfall is lost to evaporation. With only about 5%

retained as surface water. (Weinberger et al., 2012, p. 11), the

inhabitants early learned to supplement, their water supplies, e.g. "I

made myself pools from which to water the forest of growing trees." (an

orchard — Ecclesiastes 2:6).

The

remaining 25% of the rainfall finds its way into huge subterranean

aquifers, the source of water for the many wells and springs. Some of

the wells mentioned in the Bible include Jacob's Well, at Sychar in

Samaria, (John 4:5-7), Abraham's well at Beer Sheba, (Genesis

21:25-30), and at Haran (Genesis 24:`16). Some of these wells were

located in the desert, others within villages, and sometimes, as at

Bahurim (2 Samuel 17:18), within the courtyards of homes.

There

are a number of springs throughout the land; at Nephtoah (Joshua 15:9),

and Ein Gedi, west of the Dead Sea, near Masada and Qumran, and at Ein

Bokek near the Dead Sea, the latter two creating fertile oases. Places

with natural springs, e.g. "… the waters of Jericho" (Joshua 16:1)

attracted early settlers. Jericho, first settled circa 10,000 BCE, had

a number of springs, including one which produced 4,000 litres (1,000

gallons) every minute (Coogan, 1998, p. 12). Similarly, what would

later become the city of Jerusalem, began circa 4,500-3,500 BCE, when

early Canaanites settled on the eastern slopes near the Gihon Springs,

a small tributary of the Brook Kidron. (Arabic — Wady Sitti Miriam).

Running through the Kidron Valley between Jerusalem and the Mount of

Olives, (1 Kings 2:37; Nehemiah 2:15; Jeremiah 31:40), it was diverted

in 712 BCE through a culvert, the Siloam, or Hezekiah's Tunnel, to

carry water into the Pool of Siloam in the city (2 Kings 20:20; 2

Chronicles 32:3-4), to provide Jerusalem with a reliable water supply

during periods of siege.

Israel's

largest, and only permanently flowing river is the Jordan. Known to the

Arabs as Shari'at al-Kabirah ("the great watering-place") or simply

Al-Shari'ah ("the watering-place", Jacobs, 1907), it was here,

according to the New Testament, that John the Baptist laboured, "… and

they were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins."

(Matthew 3:6)

The

Jordan has three sources, "… the Leddan, the Banias, and the Hasbany."

(Leeper, 1990, p. 327) The Leddan, the largest spring in Syria, is

located near the base of a hill which was once the location of the city

of Dan. The Banias emerges from a limestone cliff near ancient Banias,

(Caesarea Philippi), and joins the Leddan some 8 km. (5 miles), south

of Dan, while the Hasbany, which rises from a valley at the western

base of Mount Hermon, joins the stream some 1.6 km. (1 mile), below the

junction of the Leddan and Banias.

Flowing

through the Great Rift Valley the Jordan enters Lake Kinneret, then,

continuing out the other side, flows through the Jordan Valley, (an

area known as the Ghor, Arabic Al Ghawr), for some 100 km. (62 miles),

before entering the Dead Sea. Although only 200 km. (124 miles), from

its source to the Dead Sea, because of its meandering course, the

Jordan is actually some 360 km. (223 miles), in length, (Jordan River,

EB, 2015).

Israel

has a relatively harsh climate. For most of the year, a fierce

unrelenting sun assails the land; even worse, the land is frequently

battered by fierce winds and sand storms. The worst of these is the

ruaḥ qadīm, (the biblical "east wind"), a destructive wind, (Psalms

48:7), which withers the crops, (Ezekiel 17:10). Called by the Arabs

khamsin, (Arabic for "fifty"), because they say the wind blows for

fifty days at a time, it is a hot wind, which can increase temperatures

as much as 20 degrees over several hours. Often reaching speeds of 140

k.p.h., (86 m.p.h. +) as it tears across the sandy wastes of the great

Wilderness, it lifts tonnes of sand and dust into the air, sweeping it

across the settled areas where the ferocious, hot stinging clouds of

sand bring agony to everyone in its path. Even in large cities like

Jerusalem, there is little relief from its fierce attack, the choking

dust invading most homes.

THE NAME:

Throughout

history the land has been known by a variety of names.

During

the period of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (2649-2150 BCE) it was known as

Haria-sha, ("the land of the sand-dwellers," Aharoni, 1978, p. 65).

According to Breasted (2001), "The Egyptians called the entire west of

Syria-Palestine Canaan" (p. 46), and reference to the "Canaanites"

first appears in a letter dated to the 18th century BCE, (Aharoni,

1978,p. 67). As Zobel (1995) noted in the Amarna tablets, the country

was referred to as "... Ki-na-aɧ-ɧi, ki-na-aɧ-ni or ki-na-aɧ-na," (p.

212). It was also called, Kananu, or Kn'n, (Astour, 1965), and, it

appears, it was from this source that the name Canaan, "... the native

name for Phoenicia" (Astour, 1965, p. 346), was derived.

There

is some uncertainty as to the actual meaning of "Canaan". As Zobel

(1995) observed, past researchers thought it meant "lowland," however

Astour (1965) discounts this etymology. Zobel (1995) mentioned other

possible meanings including, "... Occident, the Land of the Sunset or

Westland" (p. 214). Another idea was that since Phoenicia was called

"the land of purple" the name might mean "purple." (p. 214). This

related to the purple dye obtained from the snail, Bolinus brandaris,

which came from this area, and was a major item of trade.

Astour

(1965) claimed Canaan was, "... a Hurrian appellative of Phoenicia as

the country of purple dye." (p. 346), and it was by this name that it

is referred to in the Hebrew Old Testament,

"And

the territory of the Canaanites extended from Sidon in the direction of

Gerar as far as Gaza, and in the direction of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah

and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha." (Genesis 10:19)

However,

as Noll (2001) pointed out, 'Canaan' referred not only to the area of

what is now, "… roughly modern Lebanon and Israel." (p. 15), but also

to the various groups that inhabited the area. In addition to the

Canaanites there were also the, "…Amorites, Hittites, Hivites,

Girgashites, Jebusites and Perizzites." (Noll, p. 15; see Joshua 12:8)

As McNutt (1999) observed, despite their separate names,

"…there

is no clear nonbiblical evidence of ethnic distinctions among these

groups or of being culturally different from other occupants of

Palestine." (p. 35).

From

around the 16th century BCE much of the coastal area of what is now

Lebanon, Palestine, Israel and Syria came to be known as Phoenicia.

Although Tristram, (1884), claimed this was Greek for, "the land of

palm-trees", (p. 207), as previously mentioned, more recent sources,

such as Astour (1965), suggested it more likely meant, "the country of

purple dye." Later, (circa 5th century BCE), the inland area, including

the mountain district and rift valley, rather than the coastal area,

would come to be referred to by the Greeks as Palestine, a name derived

from Pelishtim, in Hebrew Pelesheth, or pelestim, the ancient name for

the land of the Philistines, and rendered as Philistia in Judges 10:6;

Psalms 83:7; 87:4.

"The

name was revived by the Romans in the 2nd century AD in "Syria

Palaestina," designating the southern portion of the province of Syria,

and made its way thence into Arabic, where it has been used to describe

the region at least since the early Islamic era. (Palestine, EB, 2015)"

The

name "Israel" per se, originates from the story told in Genesis

32:28-29; 35:10; there Jacob, (the grandson of Abraham and one of those

whom god made a covenant with), had his name changed to Israel,

(meaning "wrestle with god"). His twelve sons are said to have been the

ancestors of the Israelites, the "Children of Israel." In ancient

times, this was the name used to refer to the Kingdom of Israel and to

the Jewish nation.

The

first known reference to the name "Israel" comes from the Merneptah

stele, (circa 1209 BCE). Containing 28 lines of text celebrating the

victories of the Pharaoh Merneptah (1213-1203 BCE), the last three

lines refer to Canaan and Israel, "Canaan has been plundered … Israel

is laid waste and his seed is not."

Upon

independence in 1948, the name, the "State of Israel," was officially

adopted over Zion and Judah, other suggested names for this nation.

(Continued

in Investigator 171)

ISRAEL – THE LAND AND

ITS PEOPLE

Part

Two

Laurie

Eddie

(Investigator

171, 2016 November

THE PEOPLE

According

to the Hebrew Old Testament the Israelite settlement of Canaan began

with the descendants of Abraham and the "Out of Egypt" scenario. This

evolved from the biblical claim that seventy members of the household

of Jacob, (Genesis 46:27), had settled in Egypt and, over time, their

numbers had greatly increased. Three conflicting time-frames are given

for the increase in their numbers: -

a)

Ten generations, (430 years), [Exodus 12:40];

b)

Four hundred years, [Genesis 15:13]; or,

c)

Four generations, [Genesis 15:16).

Payne

(1963) suggests that, within this "period" their population had grown

to a figure of "almost 3,000,000"

(p. 388) which suggests this would

have been the number of Israelites who participated in the Exodus.

Although this entire Exodus saga is most likely entirely fictional,

there is some rather dubious information within the Hebrew Old

Testament supporting the claim that a very large Israelite population

was present in Egypt at that time of the claimed "exodus."

Exodus

12:37 claims there were, "... about

600,000 men on foot besides women

and children." (Numbers 1:44 puts the figure at 603,550).

Numbers 1:2-3

suggests these were only the young and fit portion of the male

population, "From twenty years old

and upward, all in Israel who are

able to go to war," — a claim repeated in Numbers 26:2.

If

one bases calculations on this figure, and, ignoring the very young and

elderly males, this suggests at least 600,000 men of marriageable age.

In turn, if we allow for a similar number of wives, we obtain a figure

of roughly 1,200,000 adult individuals.

In

ancient times, families tended to have many children, however, if we

conservatively allow for only three children per family, this would

provide a figure of some 1,800,000 children. If this figure is added to

the adult total, (ignoring any young girls and older males and

females), this suggests that at least 3,000,000 Israelites participated

in the exodus. However, it was not only the Israelites who are said to

have left Egypt, for it is claimed that others, "A mixed multitude also

went up with them." (Exodus 12:38). The absurdity of such a

large

number of individuals leaving Egypt is highlighted by the fact that, as

Butzer (1999) indicated, at the time of the so-called exodus. the

entire population of Egypt was estimated to only be around 3,000,000 –

3,500,000, (p. 297).

Most

researchers now consider the entire Exodus saga to be completely

fictional and, as such, historically worthless. Many researchers,

including Moore and Kelle (2011), cite the fact that, "…no clear

extrabiblical evidence exists for any aspect of the Egyptian sojourn,

exodus or wilderness wanderings." (p. 81) As Meyers (2005)

noted,

After

more than a century of research and the massive efforts of generations

of archaeologists and Egyptologists, nothing has been recovered that

relates directly to the account in Exodus of an Egyptian sojourn and

escape of a large-scale migration through Sinai. (p. 5)

Apart

from the complete lack of any evidence for the Exodus, many of the

incidents within the narrative are so utterly fantastic they can only

be fable. Thus, it would appear the entire saga of the exodus is simply

a collection of ancient myths and folklore, and that this oral material

was brought together, and written down, possibly for the very first

time, during the Babylonian exile, (6th century BCE), by Jewish

scholars who, in their naivety, recorded the miraculous claims without

questioning their reliability.

The

fact is, we do not know when, or where, the proto-Israelites came from.

However, rather than the Exodus account of a "huge" number of them

"invading" Canaan, it is more likely that, the Israelites evolved from

amongst various nomadic groups who were already living in, and around

Canaan, and, at some point in time, by banding together, they became

powerful enough to forcibly establish themselves as an independent

nation within Canaan.

Apart

from Africa, the Levant was one of the earliest inhabited areas in the

world. As early as 1.8 million years B.P. hominins, (Homo erectus and

Homo heidelbergensis), began migrating northwards out of Africa,

probably following the coastal plains, (later referred to as the Way of

the Philistines, or, the Via Maris, the "way of the sea").

Remains

found at Tel Ubeidiya, (3 km.

south of Lake Kinneret), and dated circa

1.5 million years B.P., suggest some of these early hominins settled in

this land. Later, others, genetically closer to Homo sapiens also

settled in this area; their remains found at Qafzeh in Lower Galilee,

(Trinkaus, 1993) and at Mount Carmel, date from around 130,000-120,000

years B.P. However, since no genetic traces of these very early

inhabitants has ever been found amongst more modern races in the area,

it appears they either died out, or else, abandoned the region.

The

current "out of Africa" theory suggests the Homo sapiens ancestors of

modern humans left Africa circa 60,000-75,000 years B.P. It is believed

some travelled via the Levant while others crossed the Bab-el-Mandeb

Strait into Yemen and Arabia, at a time when sea-levels were much lower

than at present. Some of these settled in Arabia and the Levant, while

others travelled west into Asia Minor and Europe while others moved

eastward into Asia, India, Indonesia, and Australia.

While

there could have been as few as a thousand individuals, (Stix, 2008),

over the next 60,000 or so years, as they spread across the world,

their numbers greatly increased and they formed many separate cultural

identities. As Brace (2006) noted, by the time of the Neolithic, (circa

14,000 B.P.), there was already a diverse range of populations living

within the Fertile Crescent.

According

to Mann (2011), by about 13,000 BCE, when the climate was still warm

and wet, there were already villages with several hundred inhabitants

in parts of the Levant. It appears that up to, and including the early

part of the Neolithic Era, many of these villagers combined a sedentary

farming lifestyle with hunting. In Ain Mallaha, an early Natufian

settlement, 25 km. (15.5 miles), north of the Sea of Galilee, in

addition to gathering food, they continued to hunt gazelle, fallow

deer, red deer, roe deer, wild boar, hare, tortoise, reptiles, and

fish. However, as weather patterns changed and periods of cold weather

produced widespread drought, they, and many others, were forced to make

dramatic changes to their lifestyle.

Circa

12,500 BCE a period of cold, dry weather lasting between 100-300 years

was followed by a twelve-hundred year mini Ice-Age circa 10,800 BCE The

temperature dropped some 11oC greatly reducing rainfall and the ensuing

drought-like conditions depleted crops and reduced the grasslands so

that herd numbers greatly decreased. This produced an enormous degree

of social instability. Many abandoned village life, returning to a

nomadic foraging lifestyle while those who remained in their villages

were forced to become more defensive, to protect their crops, their

limited food supplies and their villages, against wandering marauders.

Necessity

forced them to look for better ways to exploit their cereal crops. One

of their principal cereals, a species of wild einkorn wheat, had a

major problem; when its grains ripened they would spontaneously break

away from the plant to be scattered by the wind. This meant the grains

had to be picked off the ground individually so that its collection was

difficult and time consuming. Fortunately, at around this same time a

mutant form of wheat appeared. A mutation in a single gene of this

wheat produced a strain that retained its grains on the stalk when it

ripened. This made collection by hand much easier and even more

advantageous, early farmers appear to have realised that, by using

cutting tools such as sickles, they could quickly and easily collect

large amounts of this grain.

Apparently,

the first to harvest this new species were the Natufians who

established settlements in what are present day Palestine and the Golan

Heights near Lake Kinneret. While we do not know exactly when the

mutation occurred, the existence of sickles in the early part of the

Natufian culture, (12,500-11,000 BCE) strongly supports the existence

of this new species of wheat. Furthermore, since this new type of wheat

required human intervention to spread its seeds, its sudden, widespread

distribution, suggests the Natufians were responsible.

Other

major lifestyle changes came with the domestication of animals. This

freed humans from the time-consuming need to hunt, and, in addition to

a more regular supply of meat, humans now had access to additional

protein and nutrients in the dairy products these animals supplied.

Zeder (2008), suggests that circa 9,000-8,500 BCE, (or possibly

earlier), humans began to domesticate sheep and goats in south-eastern

Anatolia, and the practice appears to have spread quickly throughout

the Levant and Arabia, environments which, as previously mentioned,

were ideal for grazing these types of animals. (Coogan, 1998, p. 4)

Large

herds of sheep and goats generally require more grazing land than is

normally available around a fixed village location, and, as much of the

land provided only poor grazing, some groups, including the

proto-Israelites, adopted a nomadic pastoral lifestyle. The text,

"'Your servants have been keepers of

livestock from our youth even

until now, both we and our fathers." (Genesis, 46:34), may

reflect a

distant memory of this semi-nomadic lifestyle. Hieroglyphs on the

Merneptah stele certainly support this possibility. Redmount (1998)

noted that,

"The

hieroglyphs with which Israel was written include instead the

determinative sign usually reserved for foreign peoples: a throw stick

plus a man and a woman over the three vertical plural lines. This sign

is typically used by the Egyptians to signify nomadic groups or peoples

without a fixed city-state home, thus implying a semi nomadic or rural

status for "Israel" at that time." (p. 72)

This

observation is supported by Stager (1998) who noted that, "… Israel is

correctly distinguished as a rural or tribal entity by the

determinative for "people." (Stager, 1998, p. 91)

In

ancient times there were a number of these nomadic herding clans

located throughout the Levant, Mesopotamia and Arabia. Known by various

names, Ahlamu, Aramu, Amurru, Shasu, from the 9th century BCE, the

Assyrians began to refer to them as "Arabs" (Ephál, 1984). From

time-to-time some of them would resort to banditry, creating civil

unrest. During the reign of Seti I, (circa. 1294-1279), Shasu Bedouin,

began attacking caravans "…along the

Ways of Horus, which connected

Egypt and Gaza." and became the subject of a campaign by Seti.

(Redmount, 1998, p. 84) As Breasted (2001) noted, in an account of this

campaign, it is claimed that Set I pursued them as far as a fortified

town called pe-Kanan, ("the Canaan," p. 46).

Some,

like the Shasu, (1306 – 1292 BCE), became dominant enough to be able

to occupy much of the Levant area. (Miller, 2005, p. 95) The Amurru

clans, (Amorites), became so powerful that, by the 14th century BCE,

they had successfully invaded southern Mesopotamia, overthrown the

Third Dynasty of Ur, occupied parts of Canaan and founded ancient

Babylon. It was in the midst of this ongoing turmoil that the

proto-Israelites appear to have emerged.

According

to Redmount (1998),

"…the

Apiru, the Shasu are often invoked in discussions of Israelite origins,

and a number of scholars think that elements of the Shasu were among

the proto-Israelites who formed the core of the settlers of the hill

country of Canaan during the late thirteenth and early twelfth

centuries." (p. 84)

One

group in particular, the Habiru, (also known as, Hapiru, Abiru or

Apiru), are claimed to have actually been the proto-Israelites.

Mentioned in the Amarna tablets, (circa 14th century BCE), Barabas,

(1963), claims, "The fundamental

meaning of Habiru seems to be

wanderers." (p. 327), although Thomson, (2011), suggested that, "In

Sumerian cuneiform the word Habiru means 'the dusty-footed ones.'"(p.

xi).

Found

throughout the Fertile Crescent, the Habiru appear to have been, "…a

troublesome group of people … outlaws, mercenaries, and slaves."

(Redmount, 1998, p. 72) Marginal outcasts, with no common language or

ethnic backgrounds they existed on the fringe of Syrian and Palestinian

urban society. Wolfe (2009) claims they "…preyed upon such states."

although Thomson (2011), described them more as a, "… travelling

mercantile class" (p. xi) who bartered goods with the

caravansaries,

and were a integral part of the ancient trade system.

The

identification of the Habiru as the proto-Israelites is dubious. It is

based primarily upon the similarity of the name "Habiru" to "Hebrew",

some authors even claiming, "Habiru

is identical with the word for

Hebrew" (North, 1967, p. 22). Rainey (1995) however, suggests

this is

nothing more than wishful thinking, (p. 483).

This

common misconception arose, in part, from difficulties in translating

"consonants" in the Accadian cuneiform, (the language in which the

Amarna tablets were written). As Wolfe (2009) points out, "Hebrew" is

not the Hebrew word for "Hebrew."

The word is 'Ivri'." Whether or not

the Habiru were actually the Apiru, a term now preferred by many

scholars, or, if they were actually the ancestors of the Israelites,

remains uncertain.

While

we cannot be certain as to whom the proto-Israelites really were,

evidence suggests they were definitely one of several cultural groups

that evolved in the Middle East, possibly in the northern part of the

Fertile Crescent.

It

is likely they began as a small group, and, as was common when family

numbers increased, they divided into individual clans. Eventually they

became so numerous that, as a united force, they were powerful enough

to either take over the country where they lived, or else, to

successfully invade Canaan, "…probably

about 1250 BC … settling at

first in the hill country and in the south." (Canaan, EB, 2015).

Certainly, as McNutt, (1999) observed, by the end of the Iron Age I,

(circa 1,200 BCE), there is definite evidence of a people who, "… began

to identify itself as Israelite" (p. 35).

If

they had been already living in Canaan it is possible that many of the

so-called "invasion tales" are merely highly embellished memories of

their struggles as they sought to take control of the land. Indeed,

Stager (1998) mentions there was an old belief that, as a race, the

Israelites were indigenous to the region and that, like other

semi-nomadic groups, some of them had, "…settled down in agricultural

villages about 1200 BCE." (p. 92). Finkelstein and Silberman

(2001) go

further and suggest that, not only had the Israelites always lived in

Canaan, but they were actually Canaanites who had evolved into a

separate culture. (p. 118)

This

possibility is supported by Stager (1998) who noted that, "In the

Merneptah reliefs, the Israelites … wear the same clothing and have the

same hairstyles as the Canaanites," (p. 92). Furthermore, as

previously

mentioned, McNutt (1999), had observed that, despite their separate

names, there is no independent evidence of ethnic or cultural

differences between many of the occupants of Palestine. (p. 35)

There

seems to be little doubt the proto-Israelites originated somewhere in,

or near, the Fertile Crescent. Various researchers, such as

Santachiara-Benerecetti, et al.

(1993) Hammer et al. (2000) ,

Nebel et

al. (2001) and Atzmon et al. (2010), all agree that the Jewish race

originated from paternal ancestors within, "…a common Middle Eastern

ancestral population," (Hammer, et al. 2000, p. 6769).

Nebel

et al. (2000) noted there is definite genetic evidence that as various

groups spread throughout the Levant, there was a mixing of genes. When

the genetic background of a group of 143 paternally unrelated Israeli

and Palestinian Arabs, was compared with Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and

North Welsh Jews, the results revealed that 70% of the Jews and 82% of

the Palestinian Arab males were descended from the same paternal

ancestors.

Another

study by Nebel et al. (2001) of 526 subjects in which the Y chromosomes

(transmitted from father to son) of six Middle Eastern populations

(Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Kurdish Jews from Israel; Muslim Kurds;

Muslim Arabs from Israel and the Palestinian Authority Area; and

Bedouin from the Negev) were compared, revealed little difference

between Kurdish Jews and Muslim Kurds. In general, the Jews were found

to be genetically closer to the Kurds, Turks, and Armenians, (groups

found predominantly in northern parts of the Fertile Crescent), than to

their Arab neighbours.

REFERENCES:

Aharoni,

Y. (1979). The Land of the Bible: A

Historical Geography. Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania: The Westminster Press.

Astour,

M.C. (1965). The origins of the Terms "Canaan," "Phoenician," and

"Purple" Journal of Near Eastern

Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4, Erich F.

Schmidt Memorial Issue. Part Two (October), pp. 346-350.

Atzmon,

G., Hao, L., Pe'er, I., Velez, C., Pearlman, A., Palamara, P.F.,

Morrow, B., Friedman, E. Oddoux, C., Burns, E. and Ostrer, H. (2010).

Abraham's Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations

Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry.

American Journal of Human Genetics, June 11, 86(6), 850-859.

Barabas,

S. (1963). "Habiru." In, Merrill C. Tenney, editor, Zondervan Pictorial

Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing

House,

327-328.

Brace,

C.L.; Seguchi, N; Quintyn, CB; Fox, SC; Nelson, AR; Manolis, SK;

Qifeng, P (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and

the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form." Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences USA January, 103 (1): 242–247.

Breasted,

J.H. (2001). Ancient Records of

Egypt, The Nineteenth Dynasty. volume 3

Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Butzer,

Karl W. (1999). "Demographics". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven.

Encyclopedia Of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London: Routledge

Canaan.

(2015). Encyclopædia Britannica.

Encyclopædia Britannica

Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia

Britannica.

Coogan,

M.D. (1998). "In the Beginning: The Earliest History." In Coogan,

Michael D. The Oxford History of the

Biblical World, Oxford University

Press. pp. 3-24.

Easton,

M.G. (1897). Illustrated Bible

Dictionary. London: T. Nelson and Sons,

3rd edition.

Eph`al

I (1984). The Ancient Arabs.

Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew

University.

Finkelstein,

I. and Silberman, N.A. (2001). The

Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New

Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New

York:,

Free Press.

Hackett,

J.A. (1998). "There Was No King in Israel: the Era of the Judges". In

Coogan, Michael D. The Oxford

History of the Biblical World, Oxford

University Press. pp. 132-164.

Hammer,

M.F., Redd, A.J., Wood, E.T., Bonner, M.R., Jarjanazi, H., Karafet, T.,

Santachiara-Benerecetti A.S., Oppenheimil, A., Jobling, M.A., Jenkins,

T., Ostrer, H. and Bonné-Tamir, B. (2000). "Jewish and Middle

Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome

biallelic haplotypes." Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences

of the United States of America, June, 2000, 97: 12, 6769–6774.

Jacobs,

J., Benzinger, I. and Eisenstein, J.D. (1907). "Palestine." In,

Encyclopedia Judaica, 1907,

on-line version,

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/#ixzz1SYqG4gvN,

accessed

02/10/15

Jordan

River. (2015). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia

Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia

Britannica.

Leeper,

J.L. The Sources of the Jordan River. In, The Biblical World, volume

16, no. 5, November 1900, University of Chicago Press, 326-336.

Mann,

C.C. (2011). "The Birth of Religion." National

Geographic, June, 219;

6, 34-59.

McNutt,

P.M. (1999). Reconstructing the

Society of Ancient Israel. Louisville,

Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press.

Meyers,

C. (2005). Exodus. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Miller,

R.D. (2005). Chieftains of the

Highland Clans: A History of Israel in

the 12th and 11th Centuries B. C. Grand Rapids, Michigan:

William B.

Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Moore,

M.B. and Kelle, B.E. (2011). Biblical

History and Israel's Past. Grand

Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Nebel,

A, Filon D, Weiss D.A., Weale M., Faerman M., Oppenheim A. and Thomas

M. (2000). "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and

Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial

overlap with haplotypes of Jews". Human

Genetics; December, 107 (6):

630–641.

Nebel,

A., Filon, D., Brinkman, B., Majunder, P.P., Faerman, M., Oppenheim, A.

(2001). „The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape

of the Middle East." American

Journal of Human Genetics, (November)

63:5; 1095-1112.

North,

R. (1967). Archeo-Biblical Egypt,

Rome: Piba.

Noll,

K.L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in

Antiquity. An Introduction.

Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press.

Palestine.

Encyclopædia Britannica.

Encyclopædia Britannica 2015

Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia

Britannica, 2015.

Payne,

J.B. (1963). "Israel." In, Merrill C. Tenney, editor, Zondervan

Pictorial Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan

Publishing House, 388-395.

Rainey,

A.F. (1995). "Unruly Elements in Late Bronze Age Canaanite Society."

In, Pomegranates and Golden Bells.

Editors, Wright, D.P., Freedman,

D.N. and Hurvitz, A. Winona Lake, Indiana, Eisenbrauns, pp. 481-496.

Redmount,

C. A (1998). "Bitter lives: Israel in and out of Egypt". In Coogan,

Michael D. The Oxford History of the

Biblical World, Oxford University

Press. pp. 58–89.

Santachiara-Benerecetti

A.S., Semino O, Passarino G, Torroni, A., Brdicka, R. Fellous, M. And

Modiano, G. (1993). "The common, Near-Eastern origin of Ashkenazi and

Sephardi Jews supported by Y-chromosome similarity". Annals of Human

Genetics, January 1993, 57 (1): 55–64.

Stager,

Lawrence E. (1998). "Forging an Identity: the Emergence of Ancient

Israel." In, Coogan, Michael D. The

Oxford History of the Biblical

World, Oxford University Press. pp. 90-131.

Stix,

Gary (2008). The Migration History of Humans: DNA Study Traces Human

Origins Across the Continents. Scientific

American, July 1. p. 11.

Thomson,

G.A. (2011). Habiru: The Rise of

Earliest Israel. Bloomington, Indiana:

iUniverse Inc.

Trinkaus,

E. (1993). "Femoral neck-shaft angles of the Qafzeh-Skull early modern

humans and activity levels among immature near eastern Middle

Paleolithic hominids." Journal of

Human Evolution. 25: 393-416.

Tristram,

H.B. (1884). Bible Places: The

Topography of the Holy Land. London: The

Gresham Press.

Weinberger,

G., Livshitz, Y., Givati, A. Zilberbrand, M. Tal, A. Weiss, M. and

Zurieli, A. (2012).The Natural Water

Resources Between the

Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. Israel Hydrological

Service,

Jerusalem.

Wolf,

R. (2009). From Habiru to Hebrew: The

Roots of the Jewish Tradition.

New English Review October.

Zeder,

M.A. (2008). Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean

Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. Washington D.C. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Science, 105:33, 11597-11604.

Zobel,

H.J. (1995). k'naán, in, Theological

Dictionary of the Old

Testament. Editors, Botterweck, G.J., Ringgren, H. and Fabry,

H.,

volume 7, translated by D.E. Green. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B.

Eerdmans Publishing Company: pp. 211-228.

|